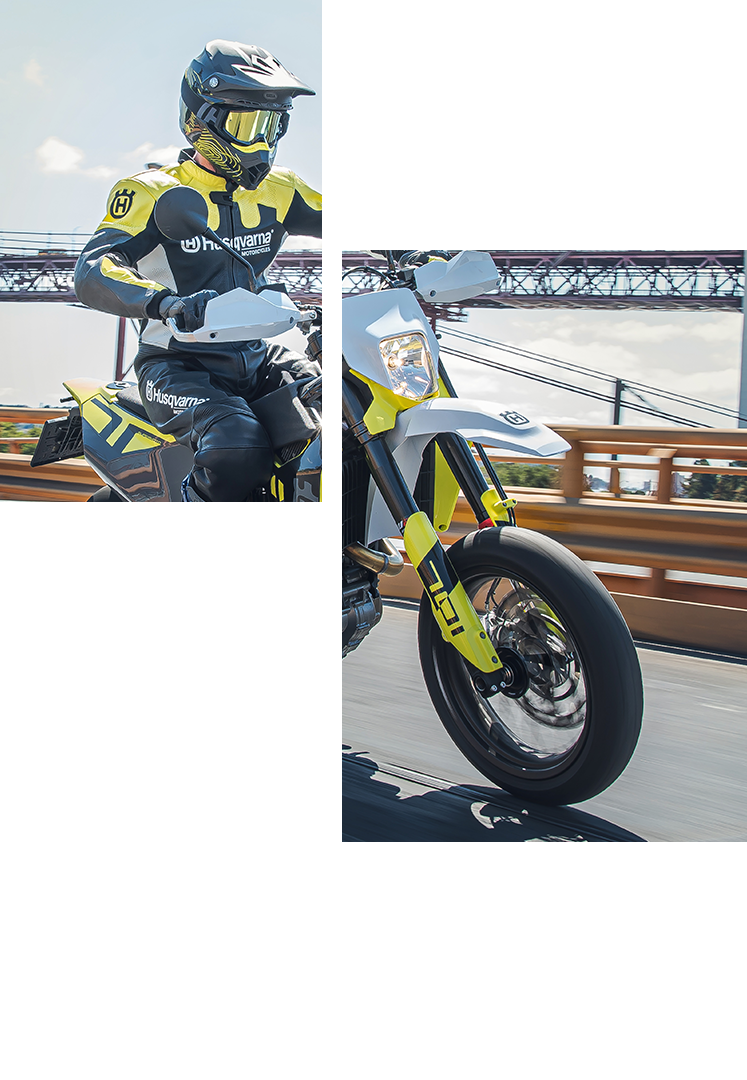

When the Swedish solo riders Gustaf Göthe, Bernhard Malmberg and David Senning each won gold medals aboard their Husqvarnas back in 1922, Sweden was put on the international two-wheel map. They came third at the fourth ISDT and gained the opportunity to organise the event on home ground the following year. Sweden said ‘thank you’ by winning the international trophy at this gruelling International Six Days Trial event, which was run under challenging conditions. The Husqvarna name was now already mentioned with awe on the continent.

Thirty years later the riders had changed from wearing miserable leather gear to riding in effective Barbour suit protection. The ‘reliability tests’ had grown in popularity and offroad racing surged immensely in the early days of the 50s. It was a relatively cheap way of competing and most people could afford this kind of racing. The rewards often consisted of honour and trophies since there was little prize money involved in offroad competition at that stage. But it was a popular sport and got people involved in motoring.